Alleluia! Christ is risen!

From the first letter of John this morning: "Everyone who loves the parent loves the child."

What apt words, and a beautiful image, for Mother's Day - a providential coincidence of our lectionary this morning - God's good sense of humor. The author of John observing that the relationship between parent and child is such that love for the one necessarily must entail love for the other; that it makes no sense to talk about loving the one without loving the the other, so deeply united are the persons of the parent and the child in their own mutual love. This is love at its contagious best, where love without condition begets love without condition: "everyone who loves the parent loves the child."

On a personal note, the providential coincidence that gives us this scripture to consider on Mother's Day is especially sweet to me because I have the especially rare gift of sharing this Sunday morning with my mother, whom I never have called "mother" but mostly "Momma," whose love for me is a gift beyond describing.

Everyone who loves the parent loves the child. In this verse's particular context within John's letter, we learn that God the Father is the Parent and Jesus is the Child; that you can't have the Father without the Son. "I am the way and the truth and the life," we remember Jesus saying. "No one comes to the Father except through me." Love of the Father necessarily entails love of the Son. And this is the beginning of the mystery we call the holy Trinity.

But John's logic isn't finished: if God the Father is the Parent and Jesus is the Child, and if everyone who loves the Parent loves the Child, John's gospel won't let us miss this important, climactic point: that in the person of Jesus, we worship the Child who makes us God's children.

We worship the Child who makes us children of God. From now on, when we hear the words, "everyone who loves the parent loves the child," we are moved toward one another. We become a people in the process of learning that love of God and love of each other have become inextricably united in the person of Jesus: the Child who makes us God's children. So now all who love God are given the privilege of loving one another.

This is how the author of 1st John can say elsewhere, "Those who say, 'I love God,' and hate their

brothers or sisters are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen. The commandment we have from him is this: those who love God must love their brothers and sisters also."

So you can't have the Father without the Son; neither can you love - and this has been a great disappointment to many people for more than 2,000 years now - neither can you love the Father and/or the Son without the tawdry group of sinners called the Church, even priests; and the Church in turn cannot truly love the Triune God without relationship with the ones outside her walls for whom Christ also died.

Everyone who loves the parent loves the child. And this room and the world are filled with the children of God.

That we are called to love one another may seem obvious. But then, that we struggle with the call to love one another should be equally obvious. As one humorous example, the 17th century French physicist, mathematician, and Catholic philosopher Blaise Pascal once wryly observed that "if everyone knew what others said about him (in his absence), there would not be four friends in the world." We can fail quite cruelly in our love for one another. There is always room for each of us and all of us to grow more deeply into the simple call to love one another as children of the God we love.

So John's epistle reminds us that God's Child has made us God's children and we as God's children have been given the holy privilege of loving all the children of God; our participation in God's love for his children is an extension of our love for the Parent. More pointedly, our participation in God's love for his children is evidence of our love for the Parent.

Having established on what grounds we ARE to love, Jesus goes on in John's gospel to describe the shape of the love we are to share with one another, and Jesus is the shape and source of the love we are called to share: "no one has greater love has this, to lay down one's life for one's friends." These words are a clear reference to what God in Jesus does for us on the cross: laying down God's own life, making us friends of God. But what can it possibly mean for us to love one another like this? To lay down one's life? And here, in these words, I think of mothers again.

I am thinking especially of the routine sacrifices that mothers learn to make like instinct in ways that leave scars and marks and wounds on their bodies, the results of loving vulnerably, even - maybe especially - when no one else notices the sacrifice or cost.

I think of Glennon Melton (no relation), an online blogger who writes hilariously and from a faith perspective about her life as a mom. Not too long ago she shared this experience - she writes:

"...last week, a woman approached me in the Target line and said the following: 'Sugar, I hope you are enjoying this. I loved every single second of parenting my two girls. Every single moment. These days go by so fast.'

"At that particular moment, Amma had arranged one of the new bras I was buying on top of her sweater and was sucking a lollipop that she must have found on the ground. She also had three shop-lifted clip-on neon feathers stuck in her hair. She looked exactly like a contestant from Toddlers and Tiaras. I couldn't find Chase anywhere, and Tish was grabbing the pen on the credit card swiper thing WHILE the woman in front of me was trying to use it. And so I just looked at the woman, smiled and said, 'Thank you. Yes. Me too. I am enjoying every single moment. Especially this one. Yes. Thank you.'

"That's not exactly what I wanted to say, though.

"There was a famous writer who, when asked if he loved writing, replied, 'No. but I love having written.' What I wanted to say to this sweet woman was, 'Are you sure? Are you sure you don't mean you love having parented?'

"I love having written. And I love having parented. My favorite part of each day is when the kids are put to sleep (to bed) and Craig and I sink into the couch to watch some quality TV, like Celebrity Wife Swap, and congratulate each other on a job well done. Or a job done, at least."

Later she adds, "But the fact remains that (one day) I will be that nostalgic lady. I just hope to be one with a clear memory. And here's what I hope to say to the younger mama gritting her teeth in line:

"'It's (hard as heck), isn't it? You're a good mom, I can tell. And I like your kids, especially that one peeing in the corner. She's my favorite. Carry on, warrior. Six hours till bedtime.' And hopefully, every once in a while, I'll add -- 'Let me pick up that grocery bill for ya, sister. Go put those kids in the van and pull on up -- I'll have them bring your groceries out.'"

Love that lays down its life. Kind of like mothers. Even when others don't see it, appreciate it, how hard it is, how much it costs. And John's gospel is thinking especially of the routine sacrifices that all followers of Jesus are asked to learn like instinct in ways that leave scars and marks and wounds on our bodies, resulting from the vulnerability of Christian love and mission, life in community, even - maybe especially - when no one else notices or appreciates the sacrifice.

It is not uncommon to hear people in the church talk about their desire for their church to feel like family. This is good news because, as we discover in John's gospel, God in Christ has loved us into God's family. That we have been made one family is also hard news because the love that has made us God's family is the love that lays down life. This is a difficult and humbling gift to receive, much less want to learn how to do. For us to learn to act in this love without sowing seeds of entitlement, self-righteousness, or resentment cannot be easy, if it is possible at all. If it is possible, it is surely and only because we know that God has become like a mother to us, that we have been reborn in Christ as daughters and sons in the Kingdom of God, where love without condition begets love without condition as we are miraculously swept up into the love that moves the sun and the stars, even the greater love of the Son. So found in the love of this Child whose Parent we love, we can seemingly do no other than seek, serve, and love the image of the Child who makes us God's children in every member of God's family. What a marvelous and unexpected gift.

Amen.

Sermon preacher on Easter 6, also Mother's Day, May 13, 2012.

"...and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations." Revelation 22:2

Showing posts with label sermons. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sermons. Show all posts

Sunday, May 13, 2012

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

On What Grounds Do We Preach One Flock?

Sermon excerpts from Easter 4, April 29, 2012

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

Today is the 4th Sunday of Easter - we’re going on a full month of Easter now, good practice in becoming an Easter people - and the 4th Sunday of Easter sometimes goes by the nickname “Good Shepherd Sunday.” We call it Good Shepherd Sunday on account of the prayer assigned to this day and the readings, especially Psalm 23 - “the Lord is my shepherd” - and our lesson from John’s gospel - “I am the good shepherd,” Jesus says.

On a personal level, I love these readings. But if I am honest, I don’t at all know what to do with these readings. In particular, I don’t know what to do with a gospel that tells us that there will be one flock and one shepherd because, this morning, I am preaching to two services at one church. Two services for somewhere in the neighborhood of seventy-five combined worshipers. If statistics prove true, fewer than half of us this morning will be among the seventy-five worshipers who show up next week, which means that our church is really made up of at least three congregations: the two that are here this morning and the one that will be here next week, plus the half of us who will join them. One flock, one shepherd, three separate assemblies. Moreover, I am preaching the news that there will be one flock and one shepherd in a town with no fewer than twenty-one churches.

Tell me: can you think of any other business, non-profit, or other public entity that the good citizens of Portland, Texas, have decided we need twenty-one of? I mean, can we get somebody as excited about bringing in some really good restaurants as our town is excited about founding new churches?

Even this number, though, gets dwarfed when one does a quick search for churches in the Corpus Christi area via the online yellow pages; such a search yields results for some four-hundred churches.

Please note that I am not saying that any of this a good thing or a bad thing; it’s simply the thing. And the thing makes me wonder on what grounds I stand before you and preach one flock and one shepherd.

Importantly, I do not think that these things necessarily mean that we Christians have missed the point of the Gospel. I cannot say for sure that we have missed the point of the Gospel because I know that each and every one of you, and me, and all of us together have very dear friends in every one of those twenty-one churches - and even at our other service (that’s a joke). Friends whom we love, friends with whom you have worked and laughed and served closely.

Still, it is a strange thing that on the morning we gather to worship the God who has made it possible for us to be friends of God and one another, we worship without many of our dear, neighborhood friends, a good number of whom are worshiping in separate buildings just down the road, even as I speak.

I know better, but - at least on the surface - rather than God making our friendships possible, it sometimes looks like Jesus gets in the way of our friendships. Like we get along better - Monday through Saturday - when we just don’t go there. And I wonder: what does it tell us about the nature of our friendships when we discover that Jesus is getting in the way of them?

Many times, as Christians, we find friendship with others as we rally together around shared causes. Causes like breast cancer, poverty, addiction, justice and wealth - and we are right, I believe, to hear God’s call to action in all of these things. We tell ourselves that it is enough that we do these things because of Jesus. We collect our friendships around these causes or lesser ones, like our children’s soccer and gymnastics practice schedules, our common love or hate of take-your-pick Texas universities, golf, biking, ceramics, whatever. And again, here we are exactly right to imagine friendships in such a way that allow us to partner with people of all types and persuasions...

And yet, I wonder if even a small part of our souls is still bold enough to hope for the possibility of friendships centered on Jesus.

....

Good Shepherd Sunday - and John’s gospel in particular - mean to call us back to the miraculous possibility of just such friendships.

The grounds for our preaching one flock and one shepherd is Jesus Christ, the Good Shepherd, who calls his sheep by name. Because he calls them to himself, he also calls them together, and he becomes their center. The flock is one because the Shepherd is one. The unity of the Church becomes a mirror of the oneness of God. This is the vision of St John’s gospel.

I do not think this vision of Christ-centered friendship means that everybody in a given church must or should be soul-mates. But I do think that all Christians should set as our goal friendships with Christ at the center. And so I feel the gentle but persuasive nudge to ask myself these questions:

Am I willing to ask my brothers and sisters here: “How is your spiritual life?” as often as I ask, “How are you?” Am I willing to listen charitably when they answer? I think of the question Cursillo small groups ask each time they gather: “When in this past week did you feel closest to Christ?” Do I offer to pray with people as often as I commit to pray for them? Do our leaders - do I as a leader - take time in the midst of our planning to ask the question out loud, “How does this plan connect to what we know about the God of Jesus Christ?” or “What image from Scripture inspires our understanding in this moment?” Do I talk to my children - whatever their age - about my own life’s direction and how I understand it in relation to God’s call? And even with folks I haven’t seen in some time, perhaps this is the question: “What has God revealed to you about who God is since last we sat down and spoke?”

I put these questions out there to hold myself accountable in asking them to you. I hope they can be questions that rescue daily life from the stale, safe, default settings. I believe they are questions of the living Kingdom and an Easter people. I hope they are questions you can use not just at St Christopher’s, but with friends in the other twenty-one churches and even in our other service.

Because Good Shepherd Sunday - and John’s gospel in particular - means to call us back to the miraculous possibility of just such friendships. Christ-at-the-center friendships. So there will be one flock, one shepherd.

Amen.

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

Today is the 4th Sunday of Easter - we’re going on a full month of Easter now, good practice in becoming an Easter people - and the 4th Sunday of Easter sometimes goes by the nickname “Good Shepherd Sunday.” We call it Good Shepherd Sunday on account of the prayer assigned to this day and the readings, especially Psalm 23 - “the Lord is my shepherd” - and our lesson from John’s gospel - “I am the good shepherd,” Jesus says.

On a personal level, I love these readings. But if I am honest, I don’t at all know what to do with these readings. In particular, I don’t know what to do with a gospel that tells us that there will be one flock and one shepherd because, this morning, I am preaching to two services at one church. Two services for somewhere in the neighborhood of seventy-five combined worshipers. If statistics prove true, fewer than half of us this morning will be among the seventy-five worshipers who show up next week, which means that our church is really made up of at least three congregations: the two that are here this morning and the one that will be here next week, plus the half of us who will join them. One flock, one shepherd, three separate assemblies. Moreover, I am preaching the news that there will be one flock and one shepherd in a town with no fewer than twenty-one churches.

Tell me: can you think of any other business, non-profit, or other public entity that the good citizens of Portland, Texas, have decided we need twenty-one of? I mean, can we get somebody as excited about bringing in some really good restaurants as our town is excited about founding new churches?

Even this number, though, gets dwarfed when one does a quick search for churches in the Corpus Christi area via the online yellow pages; such a search yields results for some four-hundred churches.

Please note that I am not saying that any of this a good thing or a bad thing; it’s simply the thing. And the thing makes me wonder on what grounds I stand before you and preach one flock and one shepherd.

Importantly, I do not think that these things necessarily mean that we Christians have missed the point of the Gospel. I cannot say for sure that we have missed the point of the Gospel because I know that each and every one of you, and me, and all of us together have very dear friends in every one of those twenty-one churches - and even at our other service (that’s a joke). Friends whom we love, friends with whom you have worked and laughed and served closely.

Still, it is a strange thing that on the morning we gather to worship the God who has made it possible for us to be friends of God and one another, we worship without many of our dear, neighborhood friends, a good number of whom are worshiping in separate buildings just down the road, even as I speak.

I know better, but - at least on the surface - rather than God making our friendships possible, it sometimes looks like Jesus gets in the way of our friendships. Like we get along better - Monday through Saturday - when we just don’t go there. And I wonder: what does it tell us about the nature of our friendships when we discover that Jesus is getting in the way of them?

Many times, as Christians, we find friendship with others as we rally together around shared causes. Causes like breast cancer, poverty, addiction, justice and wealth - and we are right, I believe, to hear God’s call to action in all of these things. We tell ourselves that it is enough that we do these things because of Jesus. We collect our friendships around these causes or lesser ones, like our children’s soccer and gymnastics practice schedules, our common love or hate of take-your-pick Texas universities, golf, biking, ceramics, whatever. And again, here we are exactly right to imagine friendships in such a way that allow us to partner with people of all types and persuasions...

And yet, I wonder if even a small part of our souls is still bold enough to hope for the possibility of friendships centered on Jesus.

....

Good Shepherd Sunday - and John’s gospel in particular - mean to call us back to the miraculous possibility of just such friendships.

The grounds for our preaching one flock and one shepherd is Jesus Christ, the Good Shepherd, who calls his sheep by name. Because he calls them to himself, he also calls them together, and he becomes their center. The flock is one because the Shepherd is one. The unity of the Church becomes a mirror of the oneness of God. This is the vision of St John’s gospel.

I do not think this vision of Christ-centered friendship means that everybody in a given church must or should be soul-mates. But I do think that all Christians should set as our goal friendships with Christ at the center. And so I feel the gentle but persuasive nudge to ask myself these questions:

Am I willing to ask my brothers and sisters here: “How is your spiritual life?” as often as I ask, “How are you?” Am I willing to listen charitably when they answer? I think of the question Cursillo small groups ask each time they gather: “When in this past week did you feel closest to Christ?” Do I offer to pray with people as often as I commit to pray for them? Do our leaders - do I as a leader - take time in the midst of our planning to ask the question out loud, “How does this plan connect to what we know about the God of Jesus Christ?” or “What image from Scripture inspires our understanding in this moment?” Do I talk to my children - whatever their age - about my own life’s direction and how I understand it in relation to God’s call? And even with folks I haven’t seen in some time, perhaps this is the question: “What has God revealed to you about who God is since last we sat down and spoke?”

I put these questions out there to hold myself accountable in asking them to you. I hope they can be questions that rescue daily life from the stale, safe, default settings. I believe they are questions of the living Kingdom and an Easter people. I hope they are questions you can use not just at St Christopher’s, but with friends in the other twenty-one churches and even in our other service.

Because Good Shepherd Sunday - and John’s gospel in particular - means to call us back to the miraculous possibility of just such friendships. Christ-at-the-center friendships. So there will be one flock, one shepherd.

Amen.

The Original Occupy Movement

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

Abide in me, Jesus says. What does Jesus mean when he says that, I wonder? The picture Jesus gives his disciples to help us understand is a vine with branches. We are the branches, and that is what Jesus says abiding looks like: branches on a vine. So one grape says to the other grape: “You know, if it wasn’t for you, I wouldn’t be in this jam.” The other grape replies: “You know I’ve about had it with you. All day long with you it’s wine, wine, wine.” (I know, I know...I'm 'pressing.')

“I am the vine, you are the branches,” Jesus says.

That we are the branches tells us that Jesus is our source and our center - and we talked about friendships centered on Jesus last week. But the image of branches is also somewhat confusing because branches do not decide to be centered on a vine - that branches are at all rests solely on the action of the vine - the vine acts and makes it so.

If a branch could un-choose her connection to the vine, not only would that branch not be a branch, the branch wouldn’t be anything else, either. She simply would not be. Everything it means to be a branch comes from being grown out of and connected to the vine - the good work of the vine. Branches are not independent agents apart from this work.

So instead of “What does it mean to abide?” maybe the question is “If we are like branches, and branches are automatically dependents of the vine - always abiding - why is abiding something Jesus has to tell us to do?” And maybe the most honest question behind both of the others is, “What is the point of abiding?”

As a beginning of the answer to that last question especially, we need to back up a bit to the chapter just before this morning’s lesson, where there’s an important back-story that today’s lesson picks up.

In chapter 14 of John’s gospel, we find Jesus telling his disciples that he is about to leave his disciples. Jesus is about to die. Jesus explains that, by the departure he will achieve through his death, he goes to prepare a dwelling place for his friends - “in my Father’s house there are many mansions (we might also use the word “rooms” or “dwelling places” here)” and the word used for dwelling places shares a root-word with our word “abide” in John 15.

Jesus goes on in chapter 14 to explain that the “room” he is preparing for his friends - which again is a twin for our word “abide” - is the gift of the Holy Spirit. Jesus leaves them in order to send his Holy Spirit. To those who love and obey Jesus’ teaching, we’re told, Jesus promises his Holy Spirit to the end that “my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him.” So “dwelling place” - which, to beat home the point, shares a root-word with “abide” - is about receiving the Spirit and having the fullness of God come make a home in the life of the one who receives it. The dwelling place made possible by the Spirit is also about our being made able to find our home in God.

It’s important, I think, that after saying all this Jesus gives his disciples his peace and tells them that, knowing these things, they do not need to be afraid.

So in chapter 14 we learn that Jesus goes to prepare a dwelling place for us, and just because he goes off to prepare it does not mean we have to go off to find it. Jesus isn’t just talking about heavenly rewards when we die. Jesus will send his Spirit to his friends, and God will make his home with them. The word for what’s being prepared is dwelling places, but the effect here is a mutual indwelling. God’s home with us and our home with God. In chapter 14, abiding is about the mutual indwelling of God and God’s friends.

And we’ve heard this kind of talk before. We hear it in our eucharistic prayers, when we pray that “he may dwell in us, and we in him.” Holy Communion is meant to be a living picture of God in us and we in God. And this is what it means to abide.

Among other things, abiding is a great relief. If abiding is about God in us and we in him, then when we abide, we are free to give up our repeated, lame, and tiring attempts to impress God, as if we could do anything good apart from him. If we do as we’ve been told to do in the gospel this morning - if we keep our home with him, abide in him - we will not have anything with which to impress God for which we will not also be moved to thank God.

And again, we’ve heard this before: in the words we say each week at the early service: “All things come of Thee, O Lord, and of Thine own have we given Thee.”

And abiding like this makes a certain kind of intuitive sense. When we welcome someone into our house, for example, and tell them to “make themselves at home” - a crude picture of what we’re calling “abiding” this morning - we are giving both parties a mutual permission not to impress one another. So I tell you to help yourself to the fridge, by which you understand that I won’t be serving you - if you want it, you get it - and also that I forego the right to complain when you take the last of my favorite beer.

There’s a tender side to this, too. Rebekah has long counted it the sign of a true friendship when a friend says, “Sure, come on over. There will be laundry on the sofa but what the heck, you’re family.”

When God pitched his tent and made himself at home with us, he certainly did not come to impress us. Isaiah tells us he was despised and rejected, that we esteemed him not. Christ’s coming among us was the beginning of the oblation - the pouring out - of himself, stooping in love, in the end washing the feet of his friends, like a slave, before his betrayal, rejection, and death.

Still, it is one thing to know this and another to live it, to enjoy freedom from the temptation - almost like instinct - to continue putting on a good show for God. “Lord, did you see that? Huh? Huh? Not so shabby - I mean, you know, for me, all things considered, if I do say so myself.”

But the mistake of our attempts to impress God is that we imagine a distance between ourselves and God that God in Christ has bridged. God is not simply interested in you; God lives inside you! Animates you! Makes his home in you. Not perfectly, certainly, but that’s the opportunity. But so often we’re all: “Yo God, did you see how I edged and manicured the lawn? Those vacuum marks are fresh.” And God is all: “mi casa es su casa.”

Now, hold on here. Does this mean that how we live our lives with God is unimportant? This question is not unlike St Paul’s question to the Romans: Should we therefore sin that grace may abound? Knowing that God doesn’t care about my laundry, should I just wear the dirty underpants? And the answer is the same as St Paul’s: Heck no!

But do you see - can you appreciate - the miracle that has been opened?

The conversation now when it happens, you and God at the table, will not be about dirty dishes or all the chores you’ve complete or smudges on the windows; it will be about the things that dear friends who have given up impressing one another talk about. Matters that matter. Come on over, appearances be darned, because there are things beneath appearances that I long to share with you. So we knock on the door or call too late. God answers the door with a yawn and a stretch. And we say, “Your presence does not simply comfort me; your presence is a challenge to me in all the best ways and toward the very best of who I had hoped to become.” Like Simon Peter, we say “You alone have the words of eternal life.” And he says to us in reply: “Make yourself at home.”

The Spirit of God making it possible for him to dwell in us and we in him.

Long before Occupy Wall Street, there was what might be called the original Occupy movement. It went something like this: “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.” The Word became flesh and literally “pitched his tent” in our camp. God made a home with humankind. We are blessed by God’s presence.

God’s abiding presence, his Holy Spirit, poured out on his people, we people, the People of God.

The lessons today teach us that, just as Easter came along unexpectedly and shouted, “Wait, wait, the cross looks like the end but this is not the end,” now we pick up the scent of Pentecost, just a few weeks off now, and it, too, is shouting: “Wait, wait, Easter looks like the end, but Easter is not the end! The power and life you saw in the risen Lord is power and life meant for you, too! Jesus himself will breathe his Spirit in you and God will make his home with you.

In your life, in my life, in the life of our church: if the Good News is that God wants to bunk up, then out, out! with everything else that gets in the way. Out with the idea that we’ve got to do this by ourselves or it doesn’t count. Out with shame. Out with fear. Out with backup plans and safety nets, like stockpiles of wealth and closets full of things we might need someday. Give them to the ones who need them now, because they need them now, and we need room.

And in this way we offer up our hands, our feet, our work, our lives, our bodies, souls, our minds, our strength, with the expectation that God in us will move them, move us, shape them, shape us, through the great and unexpected fact that God has made his home with us.

It is because this indwelling is God’s delight, purpose, and stated goal that we too seek to live lives whose delight, purpose, and stated goal is no less than this: that he abide in us, and we in him.

Amen.

Abide in me, Jesus says. What does Jesus mean when he says that, I wonder? The picture Jesus gives his disciples to help us understand is a vine with branches. We are the branches, and that is what Jesus says abiding looks like: branches on a vine. So one grape says to the other grape: “You know, if it wasn’t for you, I wouldn’t be in this jam.” The other grape replies: “You know I’ve about had it with you. All day long with you it’s wine, wine, wine.” (I know, I know...I'm 'pressing.')

“I am the vine, you are the branches,” Jesus says.

That we are the branches tells us that Jesus is our source and our center - and we talked about friendships centered on Jesus last week. But the image of branches is also somewhat confusing because branches do not decide to be centered on a vine - that branches are at all rests solely on the action of the vine - the vine acts and makes it so.

If a branch could un-choose her connection to the vine, not only would that branch not be a branch, the branch wouldn’t be anything else, either. She simply would not be. Everything it means to be a branch comes from being grown out of and connected to the vine - the good work of the vine. Branches are not independent agents apart from this work.

So instead of “What does it mean to abide?” maybe the question is “If we are like branches, and branches are automatically dependents of the vine - always abiding - why is abiding something Jesus has to tell us to do?” And maybe the most honest question behind both of the others is, “What is the point of abiding?”

As a beginning of the answer to that last question especially, we need to back up a bit to the chapter just before this morning’s lesson, where there’s an important back-story that today’s lesson picks up.

In chapter 14 of John’s gospel, we find Jesus telling his disciples that he is about to leave his disciples. Jesus is about to die. Jesus explains that, by the departure he will achieve through his death, he goes to prepare a dwelling place for his friends - “in my Father’s house there are many mansions (we might also use the word “rooms” or “dwelling places” here)” and the word used for dwelling places shares a root-word with our word “abide” in John 15.

Jesus goes on in chapter 14 to explain that the “room” he is preparing for his friends - which again is a twin for our word “abide” - is the gift of the Holy Spirit. Jesus leaves them in order to send his Holy Spirit. To those who love and obey Jesus’ teaching, we’re told, Jesus promises his Holy Spirit to the end that “my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him.” So “dwelling place” - which, to beat home the point, shares a root-word with “abide” - is about receiving the Spirit and having the fullness of God come make a home in the life of the one who receives it. The dwelling place made possible by the Spirit is also about our being made able to find our home in God.

It’s important, I think, that after saying all this Jesus gives his disciples his peace and tells them that, knowing these things, they do not need to be afraid.

So in chapter 14 we learn that Jesus goes to prepare a dwelling place for us, and just because he goes off to prepare it does not mean we have to go off to find it. Jesus isn’t just talking about heavenly rewards when we die. Jesus will send his Spirit to his friends, and God will make his home with them. The word for what’s being prepared is dwelling places, but the effect here is a mutual indwelling. God’s home with us and our home with God. In chapter 14, abiding is about the mutual indwelling of God and God’s friends.

And we’ve heard this kind of talk before. We hear it in our eucharistic prayers, when we pray that “he may dwell in us, and we in him.” Holy Communion is meant to be a living picture of God in us and we in God. And this is what it means to abide.

Among other things, abiding is a great relief. If abiding is about God in us and we in him, then when we abide, we are free to give up our repeated, lame, and tiring attempts to impress God, as if we could do anything good apart from him. If we do as we’ve been told to do in the gospel this morning - if we keep our home with him, abide in him - we will not have anything with which to impress God for which we will not also be moved to thank God.

And again, we’ve heard this before: in the words we say each week at the early service: “All things come of Thee, O Lord, and of Thine own have we given Thee.”

And abiding like this makes a certain kind of intuitive sense. When we welcome someone into our house, for example, and tell them to “make themselves at home” - a crude picture of what we’re calling “abiding” this morning - we are giving both parties a mutual permission not to impress one another. So I tell you to help yourself to the fridge, by which you understand that I won’t be serving you - if you want it, you get it - and also that I forego the right to complain when you take the last of my favorite beer.

There’s a tender side to this, too. Rebekah has long counted it the sign of a true friendship when a friend says, “Sure, come on over. There will be laundry on the sofa but what the heck, you’re family.”

When God pitched his tent and made himself at home with us, he certainly did not come to impress us. Isaiah tells us he was despised and rejected, that we esteemed him not. Christ’s coming among us was the beginning of the oblation - the pouring out - of himself, stooping in love, in the end washing the feet of his friends, like a slave, before his betrayal, rejection, and death.

Still, it is one thing to know this and another to live it, to enjoy freedom from the temptation - almost like instinct - to continue putting on a good show for God. “Lord, did you see that? Huh? Huh? Not so shabby - I mean, you know, for me, all things considered, if I do say so myself.”

But the mistake of our attempts to impress God is that we imagine a distance between ourselves and God that God in Christ has bridged. God is not simply interested in you; God lives inside you! Animates you! Makes his home in you. Not perfectly, certainly, but that’s the opportunity. But so often we’re all: “Yo God, did you see how I edged and manicured the lawn? Those vacuum marks are fresh.” And God is all: “mi casa es su casa.”

Now, hold on here. Does this mean that how we live our lives with God is unimportant? This question is not unlike St Paul’s question to the Romans: Should we therefore sin that grace may abound? Knowing that God doesn’t care about my laundry, should I just wear the dirty underpants? And the answer is the same as St Paul’s: Heck no!

But do you see - can you appreciate - the miracle that has been opened?

The conversation now when it happens, you and God at the table, will not be about dirty dishes or all the chores you’ve complete or smudges on the windows; it will be about the things that dear friends who have given up impressing one another talk about. Matters that matter. Come on over, appearances be darned, because there are things beneath appearances that I long to share with you. So we knock on the door or call too late. God answers the door with a yawn and a stretch. And we say, “Your presence does not simply comfort me; your presence is a challenge to me in all the best ways and toward the very best of who I had hoped to become.” Like Simon Peter, we say “You alone have the words of eternal life.” And he says to us in reply: “Make yourself at home.”

The Spirit of God making it possible for him to dwell in us and we in him.

Long before Occupy Wall Street, there was what might be called the original Occupy movement. It went something like this: “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.” The Word became flesh and literally “pitched his tent” in our camp. God made a home with humankind. We are blessed by God’s presence.

God’s abiding presence, his Holy Spirit, poured out on his people, we people, the People of God.

The lessons today teach us that, just as Easter came along unexpectedly and shouted, “Wait, wait, the cross looks like the end but this is not the end,” now we pick up the scent of Pentecost, just a few weeks off now, and it, too, is shouting: “Wait, wait, Easter looks like the end, but Easter is not the end! The power and life you saw in the risen Lord is power and life meant for you, too! Jesus himself will breathe his Spirit in you and God will make his home with you.

In your life, in my life, in the life of our church: if the Good News is that God wants to bunk up, then out, out! with everything else that gets in the way. Out with the idea that we’ve got to do this by ourselves or it doesn’t count. Out with shame. Out with fear. Out with backup plans and safety nets, like stockpiles of wealth and closets full of things we might need someday. Give them to the ones who need them now, because they need them now, and we need room.

And in this way we offer up our hands, our feet, our work, our lives, our bodies, souls, our minds, our strength, with the expectation that God in us will move them, move us, shape them, shape us, through the great and unexpected fact that God has made his home with us.

It is because this indwelling is God’s delight, purpose, and stated goal that we too seek to live lives whose delight, purpose, and stated goal is no less than this: that he abide in us, and we in him.

Amen.

Sermon preached at St C's for Easter 5, May 6, 2012.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Waldo, Jesus, and All Things Hiding

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

There’s this cartoon making the rounds these days in which a woman has just opened the front door of her home where she discovers two neatly dressed gentlemen with white shirts and black ties, presumably door-to-door missionaries of the Mormon or Jehovah’s Witness persuasion. The woman has opened the door to them, they stand there, the three of them, the woman and these two men, in the doorway of her house when one of the men asks the woman a question, “Ma’am, have you found Jesus?” The punchline doesn’t become evident until the reader notices a bit of robe and sandal, the hidden profile of a darkened figure, peeking out from behind the woman’s flowing set of living room curtains, some distance behind her. Apparently, Jesus was out on the lam and had taken up residence in this woman’s home.

Have you found Jesus?

On one level, this question feels distinctively Evangelical. That is, it belongs to a certain brand or flavor of Christianity. Not all Christians are comfortable talking this way. But on another level, the question “Have you found Jesus?” belongs to all of us, every one of us. One of the petitions in the Prayers of the People, Form II, asks us to pray “for all who seek God, or a deeper knowledge of him.” For all who seek God, for all who are looking for Jesus, like the woman in the cartoon.

When I hear that prayer petition, I often wonder: will I ever not seek a deeper knowledge of God? I say this without belittling the relationship I have with him. But who among us does not yearn to grow deeper in the love of the One who has loved us to the cross and beyond it? A deeper knowledge of him... In this life, at least, this prayer keeps me from complacency.

As an aside, one of the challenges for Protestant Christians, I think, is to affirm the certainty of salvation alongside and next to an abiding thirst to go deeper. One man confidently told his friend, “I don’t know about you, but I know where I’m going!” Somehow this man’s assurance had become an arrogance doing violence to the charity, the love, of the Gospel. But in the life of faith, the terms are not simply on/off, in/out, safe/not safe, but “sealed by the Holy Spirit,” “marked as Christ’s own,” “a good start, holy entrance, into a relationship of breadth and depth as we pray to dwell in him and he in us.”

We are always seeking, I suppose.

Have you found Jesus?

It’s something to think about: the way the Christian life takes on the shape of hide and seek. We are always seeking, and this can save us from complacency; but if we are not careful, it can also lead us to feelings of inadequacy or despair. As in, always seeking, never finding. The same inner urge that leads us rightly to surmise that we haven’t yet arrived might also tempt us to believe that we are not enough. So if we think of ourselves as always seeking God, we confess that some days we feel like small children, with a daunting illustration of “Where’s Waldo” before us, desperately looking for the pointy hat.

Why can’t we find the dagggum hat?

What on earth is wrong with me?

Maybe you know other Christians or friends for whom they only wish they could have found Christ hiding behind the living room curtain. But, for them, finding Jesus hasn’t proven that easy. Despite long hours in silence, prayer has not come naturally for them. Despite sleepless nights and anguished cries, your friend feels like heaven’s door for her is closed. Like she’s talking to herself and so she sometimes makes up reasons, excuses, she blames herself, in order to protect God from her doubts. Your friend may have begun believing that there is something spiritually defective in her that prevents her from finding God. Like God would make himself more accessible if she could get her act together.

Our Gospel today comes to gently challenge those who, in despair of finding God, have turned to the false medicine of self-hate. (1)

For the third straight week, beginning with Easter Sunday itself, the Gospel has spoken a story about people who are no good at hide and seek with God. People who have sought God and failed. And these people are not just any people - these people are Jesus’ very good friends. They didn’t believe when they heard it, but even when Jesus appears before them, they cannot escape their terror, fear, and doubt. In attempt to satisfy their fears, Jesus eats fish. This isn’t a ghost or hallucination or the result of their having eaten spoiled anchovies on last night’s pizza. And yet all through the gospels, as the risen Jesus returns to his friends, we find some version of what appears in Matthew’s gospel, wherein “the disciples worshiped him, but some doubted.” We sometimes tell ourselves that the life of faith would be easier if he would just come to us like he came to Thomas and the rest, but lessons like today’s lesson challenge that belief. In today’s lesson, Jesus appears to and eats with his friends, and some of them walk away at the end of the story as fearful as when it started.

But lest we get as caught up on the disciples’ failings as we get caught up on our own, let me name here the gentle challenge that these gospels mean to speak to those who, in despair of finding God, have turned to the false medicine of self-hate, and this is the gentle challenge, the main point that the gospel is making about the disciples: failures or not, Jesus has come to them. That’s the main point.

Jesus has come to them.

Love does not wait for them to get their act together. Love makes no condition for his appearing. Even when he stands before them and they fail to recognize him, their failure isn’t final, but instead becomes the starting point, the next new beginning, for the forgiveness, the mercy, and loving-kindness of God, as he patiently points back to the Scriptures, interpreting them for his friends, revealing himself to his friends. Breaking bread, eating with them. Despite their shortcomings, blind-spots, and fears, he comes to them anyway - because he loves them. And with the tenderness of a mother gently waking her children, he lovingly opens their eyes.

As it turns out, the life of faith is hide and seek, but the strange, good, glorious news of Easter and the Gospel is that we are the ones hiding and Christ is the One seeking. Unrelentingly seeking. And this Good News makes faith so much more than a hat to find on Waldo or a riddle to be solved or a task to be performed, to get just right. Faith takes the shape of a love song not from you but sung to you from the lips of the One who is head over heels for you and won’t let you go. This is the Good News of Easter. If Jesus seems hard to find, before you give up, look closer - nearer than the distant hills on which you’ve kept your gaze till now. His love requires a portrait and not a landscape lens. You need to know that you are beloved of God, and that his heart seeks you.

The revelation that faith is at least as much about Jesus finding me as my finding him inspired one anonymous poet to craft the hymn we know as #689 in The Hymnal 1982. I share it with you by way of closing:

I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew he moved my soul to seek him, seeking me; it was not I that found O Savior true; no, I was found of thee.

Thou didst reach forth thy hand and mine enfold; I walked and sank not on the storm-vexed sea; ‘twas not so much that I on thee took hold, as thou, dear Lord, on me.

I find, I walk, I love, but oh the whole of love is but my answer, Lord, to thee; for thou wert long beforehand with my soul, always thou lovest me.

So come, come one more time to the table that the Lord who sought you has also prepared for you. Break the bread, drink the cup. One more time, let him open your eyes. Be found again, alive in the love of God through Christ Jesus our Lord.

Amen.

_________

(1) And superstition, which is the belief that getting the act together would compel God to show up. But that takes as a little far afield from our main thrust here.

There’s this cartoon making the rounds these days in which a woman has just opened the front door of her home where she discovers two neatly dressed gentlemen with white shirts and black ties, presumably door-to-door missionaries of the Mormon or Jehovah’s Witness persuasion. The woman has opened the door to them, they stand there, the three of them, the woman and these two men, in the doorway of her house when one of the men asks the woman a question, “Ma’am, have you found Jesus?” The punchline doesn’t become evident until the reader notices a bit of robe and sandal, the hidden profile of a darkened figure, peeking out from behind the woman’s flowing set of living room curtains, some distance behind her. Apparently, Jesus was out on the lam and had taken up residence in this woman’s home.

Have you found Jesus?

On one level, this question feels distinctively Evangelical. That is, it belongs to a certain brand or flavor of Christianity. Not all Christians are comfortable talking this way. But on another level, the question “Have you found Jesus?” belongs to all of us, every one of us. One of the petitions in the Prayers of the People, Form II, asks us to pray “for all who seek God, or a deeper knowledge of him.” For all who seek God, for all who are looking for Jesus, like the woman in the cartoon.

When I hear that prayer petition, I often wonder: will I ever not seek a deeper knowledge of God? I say this without belittling the relationship I have with him. But who among us does not yearn to grow deeper in the love of the One who has loved us to the cross and beyond it? A deeper knowledge of him... In this life, at least, this prayer keeps me from complacency.

As an aside, one of the challenges for Protestant Christians, I think, is to affirm the certainty of salvation alongside and next to an abiding thirst to go deeper. One man confidently told his friend, “I don’t know about you, but I know where I’m going!” Somehow this man’s assurance had become an arrogance doing violence to the charity, the love, of the Gospel. But in the life of faith, the terms are not simply on/off, in/out, safe/not safe, but “sealed by the Holy Spirit,” “marked as Christ’s own,” “a good start, holy entrance, into a relationship of breadth and depth as we pray to dwell in him and he in us.”

We are always seeking, I suppose.

Have you found Jesus?

It’s something to think about: the way the Christian life takes on the shape of hide and seek. We are always seeking, and this can save us from complacency; but if we are not careful, it can also lead us to feelings of inadequacy or despair. As in, always seeking, never finding. The same inner urge that leads us rightly to surmise that we haven’t yet arrived might also tempt us to believe that we are not enough. So if we think of ourselves as always seeking God, we confess that some days we feel like small children, with a daunting illustration of “Where’s Waldo” before us, desperately looking for the pointy hat.

Why can’t we find the dagggum hat?

What on earth is wrong with me?

Maybe you know other Christians or friends for whom they only wish they could have found Christ hiding behind the living room curtain. But, for them, finding Jesus hasn’t proven that easy. Despite long hours in silence, prayer has not come naturally for them. Despite sleepless nights and anguished cries, your friend feels like heaven’s door for her is closed. Like she’s talking to herself and so she sometimes makes up reasons, excuses, she blames herself, in order to protect God from her doubts. Your friend may have begun believing that there is something spiritually defective in her that prevents her from finding God. Like God would make himself more accessible if she could get her act together.

Our Gospel today comes to gently challenge those who, in despair of finding God, have turned to the false medicine of self-hate. (1)

For the third straight week, beginning with Easter Sunday itself, the Gospel has spoken a story about people who are no good at hide and seek with God. People who have sought God and failed. And these people are not just any people - these people are Jesus’ very good friends. They didn’t believe when they heard it, but even when Jesus appears before them, they cannot escape their terror, fear, and doubt. In attempt to satisfy their fears, Jesus eats fish. This isn’t a ghost or hallucination or the result of their having eaten spoiled anchovies on last night’s pizza. And yet all through the gospels, as the risen Jesus returns to his friends, we find some version of what appears in Matthew’s gospel, wherein “the disciples worshiped him, but some doubted.” We sometimes tell ourselves that the life of faith would be easier if he would just come to us like he came to Thomas and the rest, but lessons like today’s lesson challenge that belief. In today’s lesson, Jesus appears to and eats with his friends, and some of them walk away at the end of the story as fearful as when it started.

But lest we get as caught up on the disciples’ failings as we get caught up on our own, let me name here the gentle challenge that these gospels mean to speak to those who, in despair of finding God, have turned to the false medicine of self-hate, and this is the gentle challenge, the main point that the gospel is making about the disciples: failures or not, Jesus has come to them. That’s the main point.

Jesus has come to them.

Love does not wait for them to get their act together. Love makes no condition for his appearing. Even when he stands before them and they fail to recognize him, their failure isn’t final, but instead becomes the starting point, the next new beginning, for the forgiveness, the mercy, and loving-kindness of God, as he patiently points back to the Scriptures, interpreting them for his friends, revealing himself to his friends. Breaking bread, eating with them. Despite their shortcomings, blind-spots, and fears, he comes to them anyway - because he loves them. And with the tenderness of a mother gently waking her children, he lovingly opens their eyes.

As it turns out, the life of faith is hide and seek, but the strange, good, glorious news of Easter and the Gospel is that we are the ones hiding and Christ is the One seeking. Unrelentingly seeking. And this Good News makes faith so much more than a hat to find on Waldo or a riddle to be solved or a task to be performed, to get just right. Faith takes the shape of a love song not from you but sung to you from the lips of the One who is head over heels for you and won’t let you go. This is the Good News of Easter. If Jesus seems hard to find, before you give up, look closer - nearer than the distant hills on which you’ve kept your gaze till now. His love requires a portrait and not a landscape lens. You need to know that you are beloved of God, and that his heart seeks you.

The revelation that faith is at least as much about Jesus finding me as my finding him inspired one anonymous poet to craft the hymn we know as #689 in The Hymnal 1982. I share it with you by way of closing:

I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew he moved my soul to seek him, seeking me; it was not I that found O Savior true; no, I was found of thee.

Thou didst reach forth thy hand and mine enfold; I walked and sank not on the storm-vexed sea; ‘twas not so much that I on thee took hold, as thou, dear Lord, on me.

I find, I walk, I love, but oh the whole of love is but my answer, Lord, to thee; for thou wert long beforehand with my soul, always thou lovest me.

So come, come one more time to the table that the Lord who sought you has also prepared for you. Break the bread, drink the cup. One more time, let him open your eyes. Be found again, alive in the love of God through Christ Jesus our Lord.

Amen.

_________

(1) And superstition, which is the belief that getting the act together would compel God to show up. But that takes as a little far afield from our main thrust here.

Sermon preached April 23, 2012, at St Christopher's by-the-Sea

Monday, April 9, 2012

Terrifying Good News

(an Easter homily)

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

The Lord is risen indeed,

Alleluia!

Praise God! It’s good to

see you. Good to be gathered together like this. Family and

strangers and good friends next to awkward acquaintances. All

together. All in praise. Singing Christ is alive!

Alleluia!

So this pastor is making a

visit to a dear parishioner of his parish, become homebound. “Door’s

open” she hollers, as he knocks on the door, and he comes in, finds a seat on

the couch near her reclining chair. He’s brought the blessed sacrament,

but they spend some time on the front end just catching up. As they begin

to talk, he spies a bowl of almonds on the table. He skipped lunch that

day to make time for the visit, and his stomach feels like it’s about to growl

and give him away. He helps himself to an almond. She talks.

He listens. He talks. She talks again, and all the while he’s

eating almonds. By the end of the visit, he looks at the bowl and, in

embarrassment, tells her, “I’m so sorry, I seem to have eaten through your

entire bowl of almonds.” “No, no, father, don’t be sorry,” she

says. “I’d already sucked all the chocolate off of them anyway.”

This to me is a picture of

Easter. Easter, the time of eggs and parties, bright dresses and flowers

and bunnies. God help us, the bunnies. But just what is left when

the chocolate’s sucked off?

Jesus, conceived by the Holy

Spirit, born of Mary, become a teacher, calling disciples, surrounded by

friends, breaking bread and wine with his friends, become a cult hero among the

crowd who thought he would bring holy war, become a threat to the religious and

political establishment who feared he would bring holy war, then killed on Good

Friday. Today, raised by God. This is the strange and marvelous

story of Holy Week.

This is our story with the

chocolate sucked off.

What do we do with this

story?

This morning I want to say

that it is okay if you don’t know what to do with this Easter, the

chocolate-less Easter. It’s fine to not know what it means. In

fact, as a priest and preacher going on six years now in God’s Church, I think

that to not know may be the only honest thing a person can do.

Now, some will say I’m

over-thinking the matter, that the meaning and message of Easter is obvious and

clear: He is risen! Alleluia! And that’s right. Let us sing

the praises loud and gladly. Let joy abound. Let’s make up for

forty days’ lost time and say it over and over again: Alleluia! He is

risen. Easter need not be more complicated than that.

Yet, but, and... We turn

to our gospel today. Consider the uncertain picture:

Mary and Mary and Salome have

made their way to the tomb. It’s early yet, but the Sabbath is over so

the law allows them to anoint Jesus’ body properly. They fuss on the way

about who will move the large stone from the tomb, but when they arrive, the

tomb is already open, the stone rolled away. Like coming home from

vacation and finding the back door unlocked. More than that, there’s

someone inside: a young man. The Good News of Easter begins with all the joy

and gladness of an unexpected late night visitor discovered in your house,

rifling through the fridge. These women are panicked. They are terrified.

It gets worse: the young man

fails in his attempt to comfort the women. “Be not alarmed.” You

can imagine, catching a strange man in a place as intimate as this, in the

early morning hours, and he calmly turns to you and says that: “Be not

alarmed.” This is a tomb! This looks like grave robbery. This

is desecration of the holy, disrespect for the dead! “Do not be alarmed,”

he says. “You are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified.

He has been raised; he is not here. Look around, see for yourself.

Go, tell the disciples and Peter...” Go, tell, he tells them.

And...

You would think that if the

meaning of Easter were obvious and clear, the women would have gone and

told. Instead, we’re told that they fled from the tomb, for terror and

amazement had seized them; they said nothing to anyone, for they were

afraid. Later, they briefly tell Peter. Let me ask you: How do you

briefly tell Peter the news that the man he called the Christ, the Messiah, the

Son of the living God, the man he betrayed is alive, that he’s risen? But

they manage to tell him briefly, like an older parent manages to tell a concerned

child he’s going in to have some tests run. They manage to slip it

in. They tell the disciples briefly, we’re told.

“Oh by the way...”

It isn’t until Jesus himself

meets them and sends them that they go, tell, from east to west, the sacred and

imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation.

An empty tomb is not

enough. Jesus himself must meet them. Just as he

must meet each of us. And so we gather in the place where he promises to

meet us, and we await the risen Lord.

It’s okay not to know what

comes next, after Easter. Okay if you don’t know what to do with

it. Indeed, if you told someone the story: that God was born in the

flesh, as one of us, that he lived and taught and challenged those in power,

that he was welcomed to Jerusalem as a king and, less than a week later, was

crucified on a cross, and that after three days he was raised from the dead and

appeared to his friends...If you told that story to a stranger and she nodded

her head at each point, “yes, yes, very good, I understand, yes,” you might

rightly think she wasn’t listening to you! Today is not the day of

ordinary common sense, but of the impossible possibility come alive.

The story of God become flesh,

incarnate, and killed, then risen from the dead isn’t supposed to make obvious

sense. But it means to get our

attention. It’s supposed to surprise us. To jar us. To make

us say, “Come again?” The story of God become flesh, incarnate, killed,

risen from the dead is supposed to leave us with the distinct and clear impression that we don’t

know it all - that we are not as in control of our lives or this universe as

we’d like to believe, that the story is not up to us, that in fact it might not

belong to us, that in the mystery called Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, we are

dealing with what CS Lewis famously called “not a tame lion.”

When we grow too comfortable

with the story, when we catch ourselves beginning to presume upon the story -

like it must be this way, like God didn’t choose this way on his own - we risk

losing sight of God’s outrageous act for us:

Jesus Christ is risen from the

dead!

German theologian Dietrich

Bonhoeffer gets at it this way:

"Good Friday (the day

Jesus is crucified) is not the darkness that necessarily must give way to

light. Nor is it the winter sleep or hibernation that stores and nurtures the

germ of life. Rather, it is the day when the incarnate God, incarnate love, is

killed by human beings who want to be gods themselves. It is the day when

the Holy One of God, that is, God himself, dies, really dies - of his own will

and yet as a result of human guilt, and no germ of life is spared in him such

that his death might resemble sleep. Good Friday is not, like winter, a

transitional stage. No, it really is the end, the end of guilty humankind

and the final judgment humankind pronounces on itself. And here only one

thing can help: God’s mighty act coming from God’s eternity and taking place

among humankind."

God’s mighty act: on this day

the Lord has acted. We will rejoice and be glad in it.

We take the pains to rehearse

the passion daily during Holy Week in part to learn that resurrection means the

living of the God who was dead as hell on the cross. Today is not our

celebration of sunshine or bluebonnets or tropical climates winning the day in

the course of the natural cycle of things. Today is the inexplicable,

unexpected, surprising Good News that death - our own and God’s - will not,

cannot separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

If the first women who learned

the news were startled at the tomb, how much more when Jesus came to them,

appeared to them, and said “go, tell.” The end is not the end. God

has made them characters in a play whose script belongs to God alone. No

one knows what will happen next. They are more afraid than ever.

Sometimes living can be more frightening than dying. All that not knowing.

And also with us. Terrified

and afraid. Yet they - and we -

know the one thing that matters: Jesus is alive.

The frontier ahead is known to

God, but not to us. So we will baptize Laura not into the illusion of our

own certainties, but only into the certainty of God’s love for her: the death and resurrection of Jesus. And this love beyond our knowing both

surprises and scares us.

If we are honest, we cannot

imagine death, much less resurrection. We cannot imagine peace with our

neighbor, much less the forgiveness of our enemy and an end to war, the killing

of people different from ourselves.

But we are learning to trust the imagination of God. And we dare to trust the imagination of

God on these grounds:

The same God who died for you

lives for you today.

Alleluia!

Happy Easter.

Amen.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Did St Peter Have Bunions?

(and other questions from Maundy Thursday)

I wonder if St Peter had bunions or - at the very least - smelly feet. He almost certainly had calluses. Cracked soles and calluses. That’s all but certain: all that travel, walking, talking, on unpaved, dusty roads. But bunions are admittedly a matter of speculation.

Peter, I suspect, could be hard on his feet. And his knees for that matter. Running headlong. Without the benefit of orthotics, I wonder how well the disciples did in sandals.

Did James’ feet over-pronate, like my own? Were there any flat footers among the holy twelve?

Was the strike pattern of each disciple - heel to toe or mid-foot strike - something one could discern by studying each foot?

Whatever one’s journey, the feet likely know the full burden of that journey best. Which is why in World War II and Korea, my grandfather believed that the secret to survival began with good socks.

On that night around the table with Jesus and his friends, despite his initial protest, I wonder what story St Peter’s feet had in mind to tell.

You put your history in another’s hands when you hand them your foot. That’s not always easy.

Not that most people are looking to decode it. Foot-reading is a sorry substitute for face-to-face relationship; friendship born of trust and time. But it’s true, I think, that our bumps and scars remind us of ourselves at least, and we feel a bit like open books, or naked, and so we grow self-conscious.

I wonder if this isn’t why we tend to contract out intimate exchanges like pedicures and doctors visits and even haircuts to professionals, not our friends. In the hands of a professional, a haircut is commonplace. In anyone else’s hands, my hair is an intensely personal, intimate space.

A friend of mine liked to talk about his “body bubble” - his sense of physical, personal space - the space to which he reserved the right to grant or deny access.

I wonder if Judas felt self-conscious as Jesus, having stated his intention, wrapped the towel around his waist and began to wash their feet. Was he afraid that his feet might betray the story of his brokenness, his secret intention on that night, that his feet might become a window to his soul?

Vulnerability, even the simple vulnerability of naked feet, is scary because it seems like such a slippery slope. Which is why children learn at an early age to lie about trivial things.

Hiding one’s self - that was the outcome of the very first sin: Adam and Eve, in love with God, too ashamed of themselves to be present to God. We know that these three great days of Holy Week are about Jesus undoing the sin of Adam: that Adam ate from a tree and Jesus will die on one; that Adam sentenced humanity to death and Jesus will raise in himself all humanity to eternal life with God. In three days’ time we will know these things, but consider how the undoing of Adam - or better said, the reclaiming of Adam - begins with these friends around this table and the towel tied around his waist:

Where Adam and Eve hid from God, here is the Great Physician present to his people, on his knees, tending their once-hidden wounds. Washing them clean with his hands.

The hiding is ending.

And God the Father, for his part, who has given all that he has to the Son, will take what belongs to the Son and declare it to them, these holy twelve. The hiding ends when they hand him their feet, and also as he kneels on the floor and takes off his robe. No more hiding. Second Eden.

So this is what tonight is about: God in Christ Jesus means to make them his friends. Friends of God. And he means to make the same of us.

What a wonderful and terrifying thing, to be made friends of God.

Wonderful because I had thought he would want nothing to do with me. Terrifying because I realize he will want everything to do with me, and I know so much about myself, and I know full well where his story is going, how terrifying the next three days will be, what they will cost. Terrifying because, once made God’s friend, I know I am no longer my own.

But what can I want as much as friendship with God? For what else was I made?

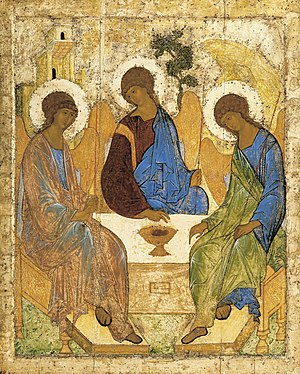

So I look up at the table, at the feast that is prepared, and Christ himself is the feast. And I think of this image.

It’s a 15th century icon of the Trinity. A picture of three strangers who appeared to Abraham and Sarah when this long pilgrimage as God’s people was only beginning. The very beginning, and these strangers came and Abraham fed them, and the early Church saw this as the clearest (maybe the only clear) depiction of the Holy Trinity in the Old Testament. And there is much that we might observe about this picture, but one thing that the church through the ages has made especially clear: that there is a spot remaining at the table - that only three sides are taken, and that we, in a sense, are already seated at the table, if pushed back a bit, reclining. And this picture of God’s people at the table with and as the family of God is what the whole story of God has been hoping for and building toward all along.

Tonight it happens. The dream of God so close we can taste it. God at table with his friends. And we are his friends. Drawn into the communion of the vulnerable. The callused. The ones with worn souls. Still here is our hope: we are no longer hidden or hiding from God, but he is binding our wounds, feeding us with himself, and giving us the strength and charge to feed one another and others with the food and drink that we find here. Bread and wine. His body. His blood. Flesh and forgiveness. The cup of forgiveness. Poured out for you.

“Love one another,” he says. “As I have loved you...”

Made friends of God, love one another.

Amen.

[Maundy Thursday sermon, preached April 5, 2012, St Christopher's by-the-Sea]

Peter, I suspect, could be hard on his feet. And his knees for that matter. Running headlong. Without the benefit of orthotics, I wonder how well the disciples did in sandals.

Did James’ feet over-pronate, like my own? Were there any flat footers among the holy twelve?

Was the strike pattern of each disciple - heel to toe or mid-foot strike - something one could discern by studying each foot?

Whatever one’s journey, the feet likely know the full burden of that journey best. Which is why in World War II and Korea, my grandfather believed that the secret to survival began with good socks.

On that night around the table with Jesus and his friends, despite his initial protest, I wonder what story St Peter’s feet had in mind to tell.

You put your history in another’s hands when you hand them your foot. That’s not always easy.

Not that most people are looking to decode it. Foot-reading is a sorry substitute for face-to-face relationship; friendship born of trust and time. But it’s true, I think, that our bumps and scars remind us of ourselves at least, and we feel a bit like open books, or naked, and so we grow self-conscious.

I wonder if this isn’t why we tend to contract out intimate exchanges like pedicures and doctors visits and even haircuts to professionals, not our friends. In the hands of a professional, a haircut is commonplace. In anyone else’s hands, my hair is an intensely personal, intimate space.

A friend of mine liked to talk about his “body bubble” - his sense of physical, personal space - the space to which he reserved the right to grant or deny access.

I wonder if Judas felt self-conscious as Jesus, having stated his intention, wrapped the towel around his waist and began to wash their feet. Was he afraid that his feet might betray the story of his brokenness, his secret intention on that night, that his feet might become a window to his soul?

Vulnerability, even the simple vulnerability of naked feet, is scary because it seems like such a slippery slope. Which is why children learn at an early age to lie about trivial things.

Hiding one’s self - that was the outcome of the very first sin: Adam and Eve, in love with God, too ashamed of themselves to be present to God. We know that these three great days of Holy Week are about Jesus undoing the sin of Adam: that Adam ate from a tree and Jesus will die on one; that Adam sentenced humanity to death and Jesus will raise in himself all humanity to eternal life with God. In three days’ time we will know these things, but consider how the undoing of Adam - or better said, the reclaiming of Adam - begins with these friends around this table and the towel tied around his waist:

Where Adam and Eve hid from God, here is the Great Physician present to his people, on his knees, tending their once-hidden wounds. Washing them clean with his hands.

The hiding is ending.

And God the Father, for his part, who has given all that he has to the Son, will take what belongs to the Son and declare it to them, these holy twelve. The hiding ends when they hand him their feet, and also as he kneels on the floor and takes off his robe. No more hiding. Second Eden.

So this is what tonight is about: God in Christ Jesus means to make them his friends. Friends of God. And he means to make the same of us.

What a wonderful and terrifying thing, to be made friends of God.

Wonderful because I had thought he would want nothing to do with me. Terrifying because I realize he will want everything to do with me, and I know so much about myself, and I know full well where his story is going, how terrifying the next three days will be, what they will cost. Terrifying because, once made God’s friend, I know I am no longer my own.

But what can I want as much as friendship with God? For what else was I made?

So I look up at the table, at the feast that is prepared, and Christ himself is the feast. And I think of this image.

It’s a 15th century icon of the Trinity. A picture of three strangers who appeared to Abraham and Sarah when this long pilgrimage as God’s people was only beginning. The very beginning, and these strangers came and Abraham fed them, and the early Church saw this as the clearest (maybe the only clear) depiction of the Holy Trinity in the Old Testament. And there is much that we might observe about this picture, but one thing that the church through the ages has made especially clear: that there is a spot remaining at the table - that only three sides are taken, and that we, in a sense, are already seated at the table, if pushed back a bit, reclining. And this picture of God’s people at the table with and as the family of God is what the whole story of God has been hoping for and building toward all along.

Tonight it happens. The dream of God so close we can taste it. God at table with his friends. And we are his friends. Drawn into the communion of the vulnerable. The callused. The ones with worn souls. Still here is our hope: we are no longer hidden or hiding from God, but he is binding our wounds, feeding us with himself, and giving us the strength and charge to feed one another and others with the food and drink that we find here. Bread and wine. His body. His blood. Flesh and forgiveness. The cup of forgiveness. Poured out for you.

“Love one another,” he says. “As I have loved you...”

Made friends of God, love one another.

Amen.

[Maundy Thursday sermon, preached April 5, 2012, St Christopher's by-the-Sea]

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Fools, Ashton Kutcher, & the Kingdom of God

(death, you've been punk'd)

For the first time in years, it has been easy for me to remember the date of Easter day. Easter day, of course, is worth remembering, especially for Christians. But for various reasons, it isn’t always easy for me to remember.

But easy this year. Easy because April 8th, Easter day, is one week after April 1st, Palm Sunday, today. And April 1st is of course also April Fools’ Day.